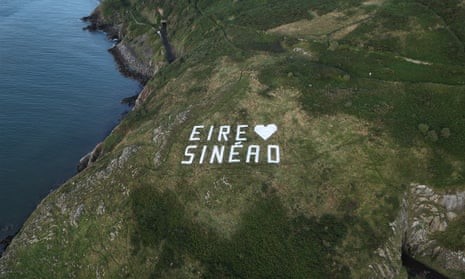

It has been a little over two weeks since news broke around the world of the passing of ground-breaking musician and political and social rebel, Shuhada’ Sadaqat, better known by her former name Sinead O’Connor, on 26 July at the age of 56. This will be a rare moment where many across the world, and perhaps all those in Ireland will have stopped in their tracks at the news of her death, and will have felt a collective grief on seeing her funeral on the news. With her funeral being just two days ago, much of this grief is still public, but the major flurry of news reports and opinion pieces have died down, giving time for a truer reflection on the artists life and her relationship with fame.

The artist became most well known with her chart-topping cover of Prince’s Nothing Compares 2 U – though from the reporting of many newspapers you couldn’t be blamed for thinking this was her only musical endeavour. As well as her pop stardom, her rebellious spirit has been remembered by the media in recent days, as have the singer’s well-documented mental health problems.

But, as a fellow Irish woman, I want instead to look at O’Connor in the tradition of protest songs, rich and significant to Irish culture. The Guardian’s reporting of O’Connor presents her as a dynamic, talented yet contradictory figure in music. While perhaps a fair analysis of a highly complex character, the article makes many insufficient, and sometimes outright disrespectful comments about the singer. One thing the author notes is that “she lacked the determination needed to keep a top-flight pop career aloft”. But O’Connor was a protest singer, and she didn’t throw away any sort of career she wanted, but the career the industry wanted for her. And there seems a lack of recognition in mainstream media circles of the strength of determination this would take.

Because not to view the defiance and bravery of the artist as just that, would be a vast underestimation of the forces which she was up against: the forces of state, religion and media. When O’Connor took on the Catholic Church in 1992 it shocked the world. The simple act of tearing up an image of the pope on television made the Catholic population of America shudder. In succession to this came a vicious backlash from the American public at a show at Madison Square Gardens, as well as an amusingly ironic criticism from the queen of pop herself, the ever so pious and Catholic, Madonna. In the immediacy of this incident on SNL and at the Bob Dylan Anniversary show, there seemed more horror at Sinead’s declaration of the Church as an enemy than what she was fighting against, the systemic sexual and physical abuse of children in the church. In the end, as would happen on more than one occasion, O’Connor was proved to be on the right side of history.

And no matter how well documented this moment is, how many references there have been to it in British and American media over these past 2 weeks, or how many times the clip is played over, what there appears to be is a lack of appreciation in British and American media circles of what this moment meant in Ireland. Ireland, who fought her way out of over 800 years of British rule, to slip straight into the iron grip of the church. This was a country where, not only was abortion and gay marriage illegal, but divorce and even contraception until 1980. But the singer risked it all to speak truth to power. Not just pop stardom and money, but the image of herself in her home country, where catholicism was intertwined with nationhood.

So maybe only the Irish will be able to truly understand how consistently brave and uncompromising she was, because certainly many obituaries from international outlets don’t seem to fully explore this with some being lacklustre at best and outright disrespectful at worst. If they recognise her as a protest singer, they fail to see what this truly meant in an Irish context. The history of protest song in Ireland is fierce, and Sinead was a rebel in the truest sense. In her early career she may not have been viewed as part of the Irish folk tradition – not all of her songs would span Irish history, and she would choose to leave Ireland for mainstream success, which as a woman at that time felt like an inevitability. But she used her voice in the most radical way she could, tackling the most significant issues of the time, constantly taking on the patriarchy in Ireland, as well as racism and poverty across the UK and Ireland, perhaps most famously on the haunting ‘Black Boys on Mopeds’.

But the love and pride she had for her country and its history would be known in her music too – and especially in the hip-hop inspired track ‘Famine’ which would trace intergenerational trauma and social issues to the Irish famine. And despite the death threats she would endure in Ireland and beyond, no serious listener of O’Connor could misunderstand her criticism of the church or the Irish government as hostility to her nation or its people. And it was the earnesty with which she so evidently cared for the nation that established how beloved she became. For a ‘pop star’ to speak of the nation’s collective trauma and the necessity for its healing, and for this voice to reach British and American audiences, was groundbreaking. For many Irish women in particular, the traumas of the Church, and especially the Laundries, was being acknowledged. Not only this, but as is tradition in folk culture, she would take on some of the greats including Raglan Road and The Foggy Dew and make them her own, cementing her legacy among some of the giants of Irish trad including Luke Kelly, The Dubliners and The Chieftains.

But despite the many in her own country who loved, admired and respected her, Sinead O’Connor would become an early victim of the ferocity of the media, and later the tumultuous nature of social media. She was mocked, nearly relentlessly, for being ‘crazy’, ‘unstable’, ‘attention-seeking’ and whatever other terms could be flung at outspoken women which would stick. She was berated for her protests, how profoundly principled she was, and how she used her fame as a platform for her social and political voice. All of these elements of her character were discussed as symptoms of her mental health. For a pop star to not ‘shut up and sing’ was outrageous, and, for the suits in the industry, intolerable. As the mainstream media remember her now, they celebrate her achievements and her talent but recognise her as a jaded and unwell woman, often viewing this as the focal point of her story, a distraction from the fact that she was a musician and woman lightyears ahead of her time, politically, socially and musically.

This isn’t to say the singer did not struggle with her mental health – this was something she did not shy away from. But quite how open she was would make the mainstream recoil: for all the talk in the present day about openness with mental health, Sinead faced a barrage of abuse for just that. Popular discourse on O’Connors mental health was Victorian, discussed as if she were ‘hysterical’, with no acknowledgement of the very real impact of her lived experiences. How her cries for help, and for justice were ridiculed and dismissed throughout her long career is a testament to the fact that even the strongest, and indeed the wealthiest of women cannot escape patriarchy. Sinead’s loss is not isolated. Its a result of the very reality of her existence – the pain and the torture suffered at the hands of the Church, and the hands of the state, and the years of torment suffered under the cruel eye of the media. She wasn’t the first and she won’t be the last. They might mourn her now she’s gone, but if you aren’t going to stand up for someone in life, why do it in death? To quote Sinead herself, “it is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

Rest in Power Sinead. I hope you have finally found peace.

Leave a comment